When people talk about yeast overgrowth in the body, they are referring to harmful yeast organisms. Candidiasis is by far the most common type of yeast infection, and there are more than 20 species of Candida, the most common being Candida albicans (a type of fungus).

We all have small amounts of Candida growing in our digestive tracts and living on our skin. This (along with other harmful gut flora, such as fungi, parasites and bacteria), is usually kept in check by our “friendly” bacteria. In this way, Candida normally co-exists with many other types of bacteria, in a state of balance in and on our bodies.

When things go wrong

It is only when our natural defences are out of balance that we become vulnerable to overgrowth – in other words, the levels of harmful gut flora that can make us ill start to exceed the number of beneficial bacteria which help to keep us well. Illness, poor digestion, a high-sugar diet and medication (such as antibiotics, which destroy both good and bad bacteria), are all examples of factors that can create the perfect environment for dysbiosis – the technical term for too many bad bugs.

In fact, yeast overgrowth is a common manifestation of dysbiosis. When the immune system is under strain, or the liver is functioning poorly, Candida (an opportunistic organism) is able to flourish. If allowed to remain, it can grow in the mucous membrane lining of the small intestine, where it can take root and cause damage. For instance, Candida can worsen any ‘leaks’ in an already inflamed gut (such as those seen in cases of leaky gut syndrome). If the yeast is permitted to enter the bloodstream, it can then also travel to various other parts of the body and promote multiple fungal infections.

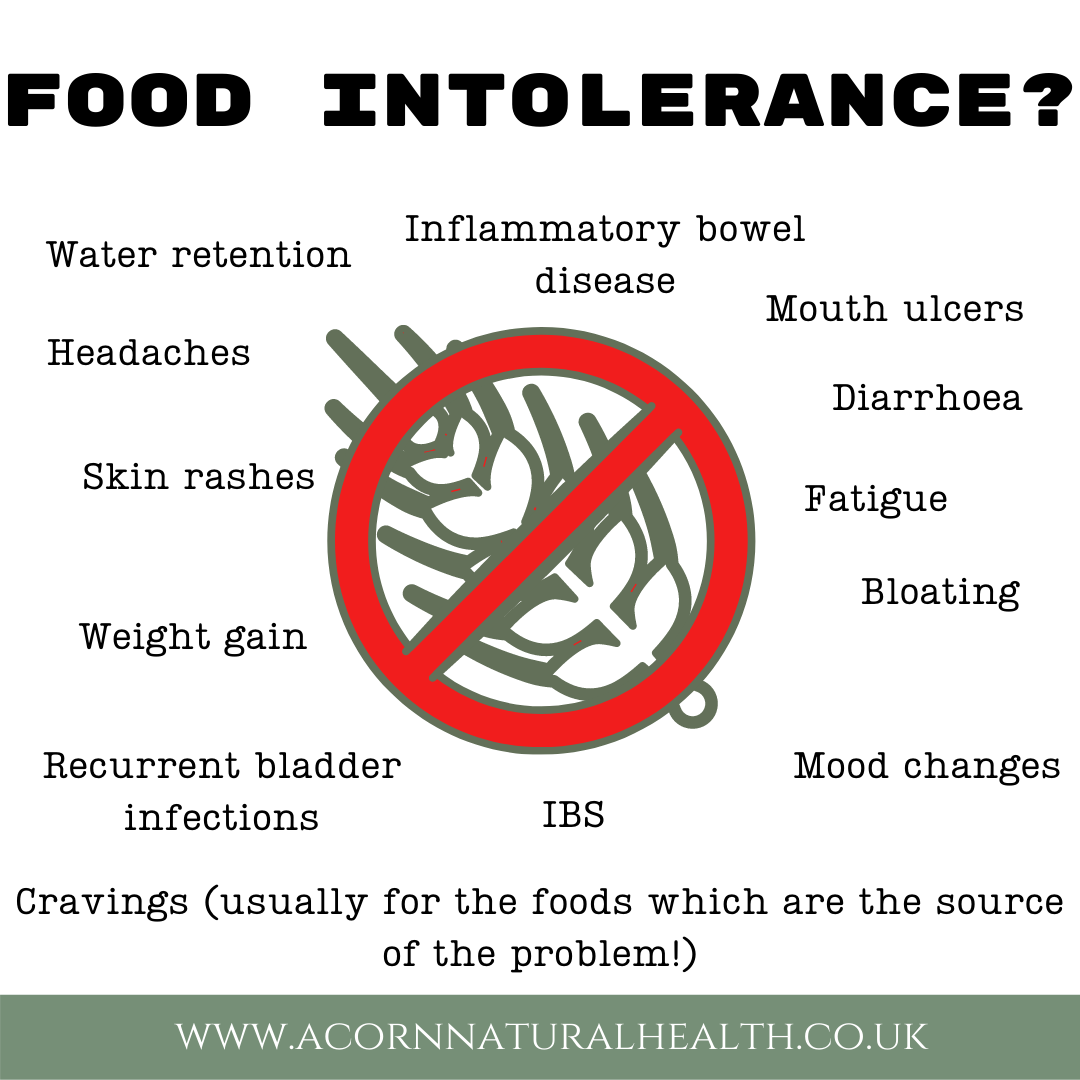

Some of the more common signs of Candida overgrowth include:

- fatigue

- sugar cravings

- brain fog

- food allergies / intolerances

- blurred vision

- depression

- digestive problems

- joint pain

- muscle pain

- chronic diarrhoea

- yeast vaginitis

- bladder infections

- menstrual problems

- and constipation.

The end result of a prolonged infection can be an immune system that becomes overwhelmed with toxins and reacts by producing antibodies and inflammatory chemicals. In these circumstances, it can be useful to review your overall lifestyle, paying particular attention to your diet, toxic load, hormonal balance and digestion – it is estimated that as much as 70% of our immune system resides in the digestive tract.

The role of diet

The average modern diet and lifestyle are not always conducive to healthy levels of gut flora and efficient digestion, which can in turn make us more prone to yeast overgrowth and a strained immune system. For example, we are exposed to an ever-increasing amount of toxins and chemicals, not least from the processed foods we eat, as well as the pollution and contaminants in the air we breathe and water we drink. It is therefore now generally accepted that people suffering from Candida albicans overgrowth can benefit from the following:

1. Eliminating certain foods and drinks from the diet, which ‘feed’ the Candida and inflame the gut: Some foods provide energy directly to the Candida yeast, while others impact the digestive system, the immune system and reduce the body’s ability to fight infection. If you want to beat Candida overgrowth and avoid it in the future, give your body the best possible chance by avoiding them. Good examples are refined sugar, white flour, alcohol, caffeine, chemical-laden processed foods, foods containing yeasts or fungi (such as mushrooms, cheese and milk) and other acid-forming foods. Wherever reasonably possible, also minimise your use of medication (such as antibiotics).

2. Incorporating more of certain foods into the diet: Just as there are certain foods worth avoiding as part of an anti-Candida diet, there are also certain foods that can support your body’s recovery, your immune system and help to restore gut health. Increase your intake of nutrient-rich fruit and vegetables (preferably raw, organic and seasonal). These natural whole foods are packed with dietary fibre, enzymes and other cleansing and protective nutrients (such as antioxidants, amino acids and phyto-chemicals). They are also naturally alkalising – a healthy balance of good and bad bacteria in the gut and a strong immune system is thought to be assisted by a diet which maintains the correct acid/alkaline balance.

3. Taking probiotics: As yeast overgrowth is often linked to an imbalance in bowel flora (as mentioned above), there is also a good case for taking probiotics (good bacteria). This can be through fermented foods or probiotic supplements. Some of the best probiotic foods include kefir, sauerkraut, miso, tofu and tempeh. If you choose to take probiotic supplements, it is a good idea to opt for high-strength, multi-strain products, with bacteria that colonise the gut.

4. Boosting the immune system: It is thought that overgrowth of yeast tends mainly to occur in those with weakened immune systems or those whose levels of good bacteria have been diminished as a result of some external factor (for instance through stress, pregnancy and/or the use of antibiotics, birth control pills or steroids).

As mentioned above, failure to promptly address a yeast overgrowth infection can lead to Candida organisms entering the bloodstream and colonising other areas of the body, such as the urinary tract, vagina, nails, mouth and skin. This level of infection can result in a chronic systemic problem, with large numbers of yeast germs further weakening the immune system and perpetuating the problem.

Candida albicans can produce around 75 toxic substances that are poisonous to the body. These toxins can contaminate tissue and weaken everything from the immune system, liver and kidneys, to the lungs, brain and nervous system. It would therefore logically be beneficial to take proactive steps to boost your immune system during a Candida infection. This might include cleansing and detoxifying your body, increasing your intake of organic whole food nutrients and (as suggested above) ensuring healthy levels of good bacteria in your gut.