A food intolerance (otherwise known as non-allergic food hypersensitivity), is a condition of the digestive system. It involves some form of negative reaction, which is caused by the body’s inability to properly digest a particular food, food additive or other compound found in food (or drink).

Food intolerances are far more common than true food allergies. They also tend to occur more commonly in women, and one reason for this may be hormone differences as many food chemicals act to mimic hormones.

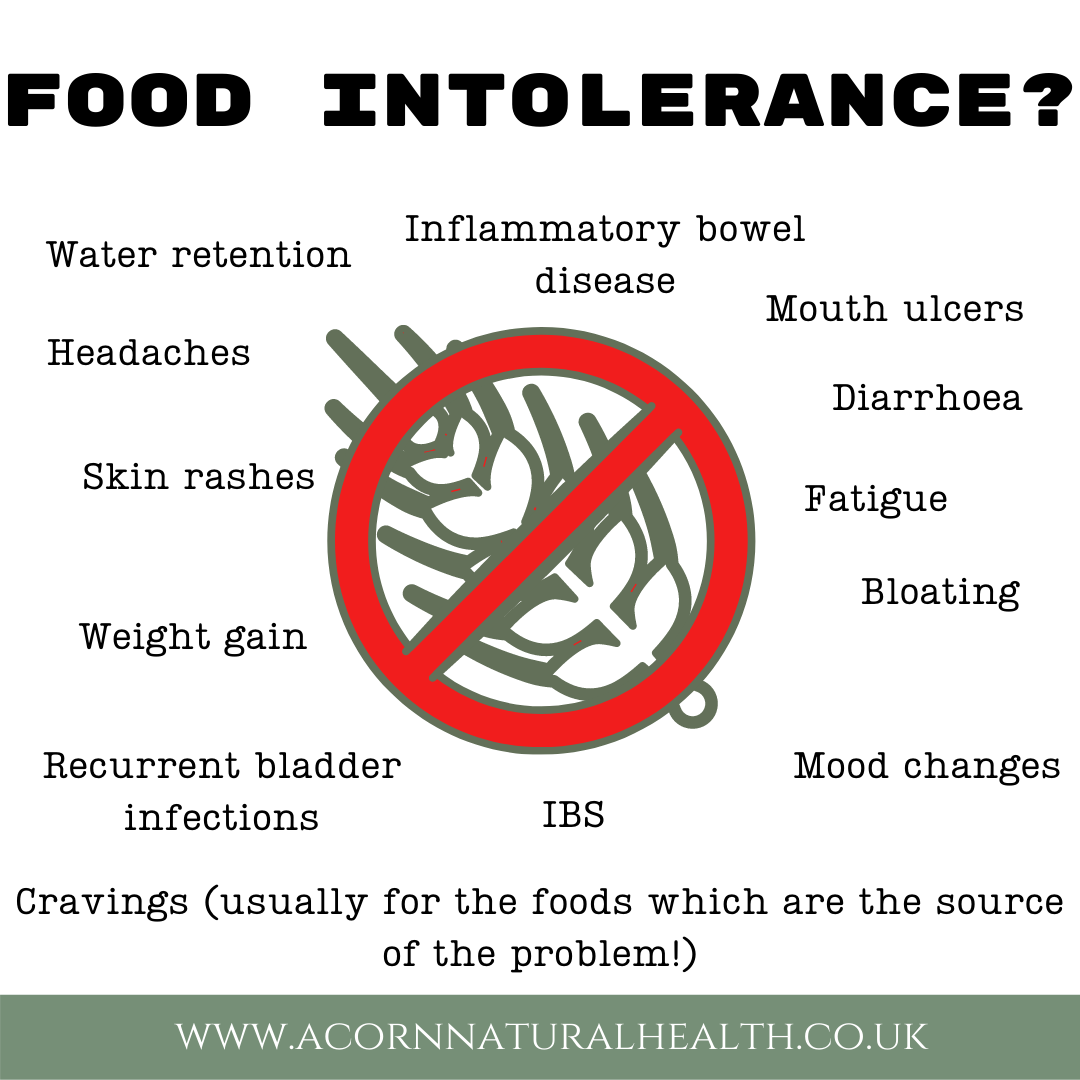

In the majority of cases, both food allergies and intolerances develop over time; so a food that was once tolerated well might suddenly begin to make you feel ill. Symptoms may begin at any age and, while they can be wide-ranging, some of the most common ones are:

- stomach bloating

- water retention

- irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- inflammatory bowel disease

- diarrhoea

- skin rashes

- weight gain

- head aches

- mood changes

- cravings (ironically, often for the foods responsible for the intolerance or allergy)

- mouth ulcers

- recurrent bladder infections

- fatigue

What causes a food intolerance?

In simple terms, food intolerances can be caused by various chemicals (both natural and artificial) that are present in a wide variety of foods. The reaction experienced is usually the result of a deficiency in, or absence of, particular chemicals or enzymes in the body that are needed to digest a particular food substance.

The role of digestive enzymes

While we eat food for the nourishment of our bodies, our digestive systems can’t actually absorb food in its whole form; instead it absorbs nutrients. So before it can be useful, food has to be broken down into its constituent parts, such as amino acids (from proteins), fatty acids (from fats) and simple sugars (from carbohydrates), as well as vitamins, minerals, and a variety of other plant and animal compounds. Without this efficient process of digestion, which converts nutrients into a form that is absorbable by the body, we would not be able to survive. Digestive enzymes are central to this process. They occur naturally in whole foods (such as fruit, vegetables and plants), but they are also manufactured by the body to assist digestion. While this mainly takes place in the pancreas and small intestine, digestive enzymes are also made in the stomach and even the saliva glands of the mouth. If you don’t eat a diet that contains enough enzyme-rich foods (e.g. a diet high in refined and processed foods), or your body does not produce enough of its own enzymes (e.g. because you are sick, elderly or under stress), it will struggle to properly break down food. This can lead to certain digestive complications and complaints, including:

- fermentation of food in the stomach and small intestine

- putrefaction in the colon

- increased activity and overgrowth of harmful bacteria and parasites

- poor absorption of nutrients.

In particular, the inability to efficiently digest food can contribute to the development of food intolerances. This is because, if you have poor digestion, your intestinal lining can become irritated and what is known as “leaky gut syndrome” can develop. In susceptible people, any partially digested food particles can seep into the bloodstream, strain the immune system and lead to food intolerances, and even allergies in extreme cases.

Food allergy vs intolerance

Food intolerances and allergies are very different. As mentioned above, an intolerance is a digestive system response. In contrast, a food allergy is an abnormal response to food, which is triggered by the body’s immune system. A true food allergy requires the presence of certain antibodies against the offending food, whilst a food intolerance does not. What’s more, the antibodies tend to lead to an immediate reaction whenever the offending food is eaten. This distinction is important because, while a food intolerance may lead to some unpleasant symptoms, it is not life-threatening and symptoms tend to come on more gradually – usually within half an hour, but sometimes as long as 48 hours after ingestion of the substance which is causing a problem. An allergy, on the other hand, is usually a lot more serious and may even be fatal in extreme cases (e.g. through anaphylaxis).

Some common examples of food intolerance include:

- Lactose intolerance – The most common food intolerance is to lactose, found in milk and other dairy products. It is caused by the body’s inability to properly digest high amounts of lactose, the predominant sugar in milk, because of a shortage or absence of the enzyme lactase.

- Gluten sensitivity – Gluten is a protein composite found in foods processed from wheat and related species, including barley and rye. The term “gluten sensitivity” is used to describe those individuals who can’t tolerate gluten and experience symptoms similar to those with coeliac disease, but yet lack the same antibodies and intestinal damage as seen in cases of coeliac disease. Interestingly, although coeliac disease is an autoimmune disorder caused by an immune response to gluten, it can also result in gluten sensitivity, as well as temporary lactose intolerance.

How is food intolerance identified?

Food intolerances are often more difficult to diagnose than food allergies, because they tend to be more chronic, less acute and therefore less obvious in their presentation. For example, there are no antibodies present to look for. As such, they are most often identified through a simple trial and error approach – a dietitian or nutritionist will go through a process of elimination with the individual, removing suspected problematic foods and systematically re-introducing them back into the diet, looking for corresponding improvement and worsening of symptoms. Bioresonance testing is another, much faster method of identyfying any potential food intolerances with results usually available at the time of testing. Other methods of diagnosis include hydrogen breath testing for lactose intolerance and fructose malabsorption and ELISA testing for IgG-mediated immune responses to specific foods.

Living with a food intolerance

Once the offending food or foods have been identified, the best advice is to avoid them wherever possible or to embark on a desensitizing treatment. This is likely to lead to a reduction, and hopefully over time, the total elimination of symptoms. Fortunately, nowadays there are a number of specialised “free from” foods and health supplements available online, in supermarkets and in health food shops, which help to make life a lot easier for those with food intolerance. However, with any diet where there is restricted food choice, it is important to ensure that you are still getting all of the nutrients you need on a daily basis. Severe food intolerance can, for example, lead to excessive weight loss and, occasionally, can even result in the individual becoming malnourished. Optimum nutrition can be achieved through careful meal planning and appropriate supplementation.